TOO MUCH OR TOO LITTLE? DISORDERS OF AGENCY ON A SPECTRUM Download PDF

Valentina Petrolini (University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU))

© 2020 Valentina Petrolini

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31820/ejap.16.2.4

Original scientific article – Received: 18/7/2020 Accepted: 22/8/2020

ABSTRACT

Disorders of agency could be described as cases where people encounter difficulties in assessing their own degree of responsibility or involvement with respect to a relevant action or event. These disturbances in one’s sense of agency appear to be meaningfully connected with some mental disorders and with some symptoms in particular—i.e. auditory verbal hallucinations, thought insertion, pathological guilt. A deeper understanding of these experiences may thus contribute to better identification and possibly treatment of people affected by such disorders. In this paper I explore disorders of agency to flesh out their phenomenology in more detail as well as to introduce some theoretical distinctions between them. Specifically, I argue that we may better understand disorders of agency by characterizing them as dimensional. In §1 I explore the cases of Auditory Verbal Hallucinations (AVH) and pathological guilt and I show that they lie at opposite ends of the agency spectrum (i.e. hypoagency versus hyperagency). In §2 I focus on two intermediate cases of hypo- and hyper- agency. These are situations that, despite being very similar to pathological ones, may be successfully distinguished from them in virtue of quantitative factors (e.g. duration, frequency, intensity). I first explore the phenomenon of mind wandering as an example of hypoagency, and I then discuss the phenomenon of false confessions as an example of hyperagency. While cases of hypoagency exemplify situations where people experience their own thoughts, bodies, or actions as something beyond their control, experiences of hyperagency provide an illusory sense of control over actions or events.

Keywords: Agency; auditory verbal hallucinations; guilt; mind wandering; false confessions

Introduction

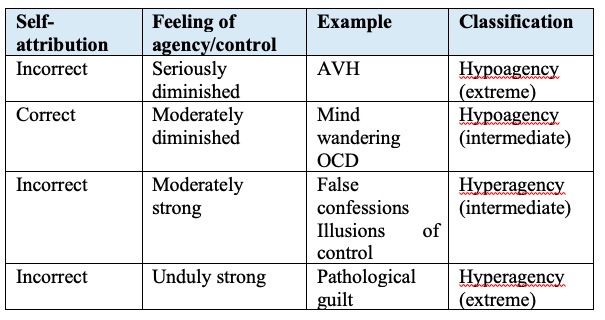

The sense of agency of an individual is normally characterized in terms of self-attribution and self-ascription and is usually connected with an appropriate assessment of one’s actions. Feelings related to agency importantly include the sense of being able to do something, of being the agent of an action (Proust 2013), as well as the sense of being in control (Pacherie 2008). These capacities allow individuals to correctly determine the scope of their thoughts and actions, and also to reliably distinguish between self-generated and other-generated stimuli. When assessing one’s sense of agency, it is important to distinguish between the correctness of self-attribution and the subjective feeling of agency or control.[1] With respect to the former, one may self-attribute agency concerning the things she has not done or fail to self-attribute agency concerning the things she has in fact done. In other words, self-attribution may be correct or incorrect. By contrast, the feeling of agency or control comes in degrees: one may be more or less sure or confident about having performed an action. Disorders of agency could thus be described as cases where people encounter difficulties in the two senses just described. On the one hand, they may experience issues in terms of self-attribution and thus fail to correctly determine whether they performed the relevant action. On the other hand, they may experience a diminished (or unduly strong) feeling of agency or control. As I show later in the paper, there are cases in which these two senses of agency come apart and others in which they go together.

In this paper I first characterize disorders of agency as lying on a spectrum. I then show that disturbances at both ends of this spectrum are connected to some mental disorders. On the one hand, a person may be unsure of whether she initiated an action that others attribute to her, or she might deny having done so despite evidence to the contrary. I call this kind of disturbance hypoagency. Extreme cases of hypoagency encompass phenomena such as auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH henceforth), thought insertion or alien hand syndrome, where people experience their thoughts or bodies as something acting beyond their control. On the other hand, a person may feel that events that are completely unrelated to her actions (or thoughts) fall under her own responsibility and therefore experience unbearable guilt as a result. This happens at times with schizophrenic individuals, who tend to blame themselves for natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or murders committed by others. In these cases, subjects attribute to themselves a greater degree of agency and control than they actually possess, thereby exhibiting hyperagency. As I explain in more detail below, in both cases an underlying sense of agency appears to be compromised. On the one hand, extreme cases of hypoagency exemplify a situation in which self-attribution of agency is incorrect (i.e. thoughts and bodies are not experienced as one’s own) and the subject lacks a robust feeling of agency or control. On the other hand, extreme cases of hyperagency exemplify a situation in which self-attribution is also incorrect—albeit in the opposite direction (i.e. one believes to have performed actions that she has in fact not performed)—but the subject reports a strong feeling of agency.

The paper is structured as follows. In §1 I explore the cases of AVH and pathological guilt and I explain how they lie at opposite ends of the agency spectrum. In §2 I focus on two intermediate cases of hypo- and hyper- agency: these are situations that—despite being very similar to pathological ones—may be successfully distinguished from them in virtue of quantitative factors. As an intermediate case of hypoagency I explore the phenomenon of mind wandering, where intrusive thoughts, memories, and feelings tend to pop up and interfere with the completion of other tasks. As an intermediate case of hyperagency, I discuss the phenomenon of false confessions, where people end up pleading guilty for crimes they did not in fact commit.

1. Hypoagency and Hyperagency: Extreme Cases

1.1 Hypoagency: Auditory Verbal Hallucinations (AVH)

Disorders of hypoagency can be characterized as situations in which a person loses grip over her own thoughts or actions, thereby experiencing them as alien and beyond her control. One extreme example is the occurrence of AVH, also known as “hearing voices”. Although there is evidence that these experiences are frequent in non-clinical populations (Johns et al. 2014; Allen et al. 2006), as well as in depressive disorders (Toh et al. 2015), AVH are often taken to represent one of the hallmarks of schizophrenia (Henriksen, Raballo and Parnas 2015). Many researchers have suggested that AVH would result from failures in self-monitoring mechanisms (Frith 1992; Jones and Fernyhough 2007). These views characterize self-monitoring issues as failures to correctly predict action outcomes in several domains, such as motor behavior (e.g. self-tickling), cognition (e.g. planning difficulties), or inner speech (e.g. AVH). Issues with self-monitoring are also likely to affect cognitive control and executive functioning at various levels, from implementing basic goals to carrying out higher order plans (Petrolini, Jorba and Vicente 2020). Applied to inner speech production, these difficulties may particularly affect what has been labeled “dialogic inner speech” (Fernyhough 2004), which refers to the conversations we have with ourselves. In this respect, inner speech in people experiencing AVH exhibits peculiar characteristics. For instance, AVH subjects appear to experience more intrusions in inner speech, often in the form of other people being present (Alderson-Day et al. 2014). Many describe the voices as exhibiting a markedly “alien” character and as differing sharply from first-person inner speech (Nayani and David 1996). People experiencing AVH also tend to appraise their inner speech as more negative (Hugdahl et al. 2012), dystonic—i.e. failing to align with the person’s self-attributed thoughts and emotions (Lopez-Silva 2016), and fragmented—i.e. distributed across more than one “voice” without being temporally coordinated or synchronized (Langland-Hassan 2008). Besides their relevance to inner speech, AVH showcase relevant facts about agency (Proust 2006) and ownership (Maiese 2015). Notably, they qualify as an experience in which sense of agency (i.e. X is caused by me, I am the author of X) and sense of ownership (i.e. X is mine, X is part of my experience) come apart. Indeed, in AVH subjects experience voices as alien—thereby denying authorship—but still as occurring within their bodily or mental boundaries in some significant sense—thereby preserving ownership (Proust 2013). In other terms, AVH experiences exhibit self-misattribution as well as a diminished sense of agency or control.[2]

A more detailed phenomenology of AVH may be garnered through the first-person account offered by Longden (2013). In her vivid report about the experience of “voice-hearing”, Longden recalls the first appearance of this phenomenon during her early college years. She describes her younger self as struggling with severe anxiety and worries about the future, but also as exhibiting a strong tendency towards suppressing her feelings. The first voice makes its appearance one evening while Eleanor is going home after a class: she characterizes it as neutral, similar to her own voice but narrating all her actions in third person, like a running commentary—e.g. “She is leaving the room”; “she is opening the door”. In the following weeks voices grow in number and intensity, becoming more persistent and menacing: in particular, they start threatening Eleanor and make her comply with a series of bizarre tasks with the promise of “getting her old life back”. These tasks are experienced by Eleanor as some sort of “Labors of Hercules” over which she has absolutely no control, but that she nonetheless feels forced to carry to completion. She describes them as initially quite small (e.g. pull out a few strands of hair) but then as progressively more extreme (e.g. harm yourself) or violating social norms (e.g. pour a glass of water on the head of the instructor during a lecture). Notably, she experiences overwhelming feelings of powerlessness because she lacks the resources to exercise any form of control over the voices. Her agency appears so compromised that at one point she attempts suicide by trying to drill a hole in her head in order to get the voices out.

The second part of Longden’s report is devoted to her process of recovery, which begins once she gets in touch with the UK-based Intervoice movement, founded in 1988 by psychiatrists Romme and Escher. The tenet of this therapeutic movement consists in claiming that voices should be treated as experiences rather than symptoms, and that the content of the voices often provides important insights into the person’s life story and personality. The primary goal of this approach is not to get rid of the voices per se, but to accept them while learning a series of coping strategies focused on “taking the power back” from them. The turning point towards recovery consists in realizing that voices may be appropriate responses to traumatic life experiences (e.g. childhood abuse) or ways to get in touch with one’s repressed emotions. For Longden this was clearly the case. During therapy she realizes that many of the voices—especially the more aggressive ones—were mirroring her hidden emotions: “Whenever I repressed anger (and that happened very often) the voice sounded frustrated” (Longden 2013). Another patient describes this phenomenon as follows:

“When the voices said: “See how awful she looks”, it happened on days when I felt myself pretty awful. But they always made such exaggerated statements. By exploring this I started to realize that in a certain way the voices expressed my own thoughts. It is rather strange, but they are your own thoughts about an emotion.” (Romme and Morris 2013, 263-264)

The treatment proposed by Romme and Escher appears particularly interesting for our purposes because it focuses on coping strategies to regain control over the voices (Romme and Escher 1993). Indeed, it could be seen as a way to enhance agency in people that experience a significant diminution in their power of controlling their mental events. Romme and Morris (2013) characterize recovery as a process of progressively gaining control over the voices by creating a dialogue with them, while at the same time setting boundaries and avoiding being overwhelmed. Romme and Escher’s approach thus appears to counter hypoagency by strengthening a sense of familiarity with the voices. The more the patient learns to incorporate the voices in her experience and to treat them as legitimate (or at least revealing) aspects of her personality, the more agency over them is restored.

2.1 Hyperagency: Pathological Guilt

Pathological guilt represents an extreme case of hyperagency which is commonly experienced by people suffering from depression, although it may also be present, albeit in a different form, in schizophrenic patients. People experiencing pathological guilt tend to feel responsible for things that they have not done or feel deeply disturbed by actions and thoughts that are regarded as innocuous by others. What these cases have in common is the subject’s inability to properly assess the scope of their (moral) responsibility. Pathological guilt may manifest itself in different ways. Some people with schizophrenia attribute to themselves actions for which they are in fact not responsible—e.g. a murder that someone else committed. For example, Saks (2007) reports being filled with anxiety when reading the newspaper because she would blame herself for every violent crime reported in the area. Alternatively, some people suffering from depression assign a particularly negative valence to self-generated thoughts and events—e.g. feeling extremely guilty about finding another person annoying. Unlike AVH experiences, cases of pathological guilt combine incorrect self-attribution with an exaggerated feeling of agency or control over the relevant action or event.

One interesting example comes from one of Freud’s earliest case histories, Emmy von N. (Freud and Breuer 1893, 48-105). Frau Emmy is a 40-year-old woman who suffers from recurring hallucinations and from a number of tic-like movements, in particular an idiosyncratic “clacking sound” that would come up whenever she is anxious or frightened. While analyzing her case, Freud notices that the patient tends to be overly hard on herself and to feel directly responsible “for the least signs of neglect”: “If the towels for the massage are not in their usual place or if the newspaper for me to read when she is asleep is not instantly ready to hand” (Ibid., 65). One day, Freud arrives to the patient’s house to continue the therapy and finds her in a state of great distress, repeating: “Am I not a worthless person? Is it not a sign of worthlessness what I did yesterday?” Freud cannot recall what happened the day before to justify such a “damning verdict” (Ibid., 70). Despite Freud’s repeated admonitions not to feel guilty over small things, Emmy keeps behaving like “an ascetic medieval monk, who sees the finger of God or the temptation of the Devil in every trivial event of his life and who is incapable of picturing the world even for a brief moment or in its smallest corner as being without reference to himself” (Ibid., 66). Notably, after a two-year long therapeutic process, Emmy is able to recover from the majority of symptoms—i.e. hallucinations, tics—but her inclination to torment herself over “indifferent things” never vanishes completely.

More recent accounts of melancholia—such as the one offered by Radden (2009)—suggest that Freud contributed to conceptualize depression as a state of mind characterized by self-criticism, where “dissatisfaction with the self on moral grounds” and “delusional expectation of punishment” stand out among the most typical clinical features (Freud 1917, 153). This point allows us to connect extreme forms of hyperagency with disturbances in one’s sense of confidence. Indeed, diminished confidence may play a role in over-attributing guilt to oneself in the face of negative events (e.g. “It happened to me because I am bad person”). It is thus unsurprising that pathological guilt is often found in the context of depressive disorders, in which self-loathing tends to feature prominently (see Plath 1963; Styron 1991 for some first-person accounts).

The pervasive presence of guilt feelings in some psychiatric disorders has also been explored by authors working in the field of psychology and philosophy of emotions. Frijda (1985), for instance, connects guilt with the sense of being in control: “[Guilt feelings] may provide an explanation for one’s misery, an explanation that provides an aspect of controllability, some shred of it, in the morass of helplessness; it permits acts of contrition and efforts at paying penance” (Frijda 1985, 431). In this sense, hyperagency may arise as an attempt to control and therefore justify or explain feelings of worthlessness and helplessness experienced in depression. Ratcliffe (2010) rather characterizes depressive guilt in terms of depth. As opposed to a circumscribed feeling of guilt about a specific action or event, depressed subjects tend to experience guilt as an “all-encompassing way of being” (Ratcliffe 2010, 609). First-person reports of depressed patients support this idea: “The reason my life is so awful at these times is because I am a terrible, wicked, failure of a person”; “Everything that goes wrong in my life is directly my fault” (reported by Ratcliffe 2015, 135. Italics mine). In these cases—such as Freud’s patient Emmy—guilt shapes one’s perception and appraisal of other people, objects, and events. In this sense, pathological guilt shares important similarities with delusional beliefs: one’s belief of being responsible brings about an experience of reality in which environmental stimuli are overwhelmingly interpreted in light of such conviction (Bortolotti and Miyazono 2015).

In the next section I discuss some intermediate cases of hypo- and hyper- agency. Although these examples bear important similarities to the ones analyzed in §1.1. and §1.2., I show that they may be successfully distinguished from them by appealing to quantitative factors (e.g. duration, frequency, intensity). As an example of hypoagency I introduce phenomena such as distraction and daydreaming, where the sense of control over one’s thoughts appears moderately diminished. As an example of hyperagency I discuss the phenomenon of false confessions, in which people over-attribute responsibility to themselves to the point of accepting punishment for crimes they did not commit.

2. Hypoagency and Hyperagency: Intermediate Cases

2.1 Hypoagency: Mind Wandering

Phenomena like distraction, daydreaming or mind wandering are extremely common in our everyday experience. We are working on an important project and we suddenly start thinking about the grocery list or our plans for the evening. We try to concentrate on a task when memories pop up and absorb us for some time before we are able to resume our previous activity. In most cases these thoughts arise automatically and are difficult to regulate. They can be seen as paradigmatic cases of hypoagency in which self-attribution is correct but the feeling of agency appears at least moderately diminished.

Despite their pervasiveness in our ordinary life, phenomena of mind wandering have only recently become the object of systematic scientific investigation, mostly due to the growing number of neuroimaging results about brain activity in rest conditions. This neural pattern has come to be known as the Default Mode Network (DMN henceforth) and its discovery suggests that mind wandering might constitute a psychological baseline from which people depart when engaging in demanding tasks and to which they return when their attention is not allocated elsewhere (Mason et al. 2007; Andrews-Hanna 2012). Although cases of excessive mind wandering have been at times granted pathological status (Schupak and Rosenthal 2009), this phenomenon has also been associated with an increase in creativity and problem-solving abilities. Indeed, the neural profile of brains in DMN is similar to the one exhibited by subjects engaged in conceptual processing and problem-solving tasks (Smallwood and Schooler 2006). In the past decade, researchers working in different fields—philosophy of mind, psychology and neuroscience in particular—have attempted to shed light on the nature of mind wandering while formulating hypotheses of its adaptive value. Mind wandering has been also characterized as a form of “mental autonomy loss” because of its spontaneous, automatic and task-unrelated nature (Metzinger 2013). The notion of mental autonomy proposed by Metzinger partially overlaps with what I call agency in this paper, and comprises the ability to causally determine one’s actions (self-attribution) as well as the ability to control the conscious content of one’s mind (feeling of agency or control). Due to the ubiquitous interruptions caused by mind wandering, Metzinger suggests that we should regard mental autonomy as “the exception rather than the rule” (Metzinger 2013, 5).

On this view, mind wandering has several advantages, such as allowing individuals to maintain a baseline arousal activity where past, present and future mental events hang together in a (virtually) unitary whole. Similarly, mind wandering has been connected with a number of positive effects on psychological functioning, such as consolidating memories, planning future events and delaying gratification (Smallwood and Andrews-Hanna 2013). This activity thus appears to grant the mind some freedom from the “here and now” and allows agents to perform mental actions that are not simply responses to the outside world. If this is correct, it becomes easier to see how mind wandering might be connected to creative and problem-solving processes. In a recent study on the topic, Baird et al. (2012) assigned the Unusual Uses Task (UUT) to 145 participants, asking them to generate as many uses as possible for a common object (e.g. a brick) in a given amount of time. After having read the list of objects, three groups of participants were subject to an incubation period during which some subjects were administered a demanding task, others an undemanding task and still others were allowed to rest. A fourth group proceeded to solve the problem without taking a break. The results indicate that participants engaging in the non-demanding task during the incubation period performed significantly better than the ones who were assigned a demanding task, no task at all or that did not have an incubation period (Baird et al. 2012, 5). The researchers suggest that engaging in a simple task allowed participants to mind wander during the incubation period and this in turn helped them formulating more creative solutions to the UUT.

As I suggest above, mind wandering can be regarded as a paradigmatic instance of hypoagency. It typically starts out as an automatic and spontaneous mental phenomenon over which we have little control. Moreover, we often have a hard time accounting for the content and origin of thoughts generated during mind wandering (e.g. when a song is stuck in our head). Notably, an instance of mind wandering may act as detrimental or beneficial from a psychological viewpoint: in other words, mind wandering exhibits a dual nature.[3] Let us assume that I have an important interview coming up and that I cannot concentrate on my PowerPoint preparation because my thoughts keep drifting away. Our discussion shows that this particular instance of mind wandering may acquire different valence depending on the context. On the one hand, external circumstances (e.g. how competitive the interview process is), my current emotional state (e.g. anxiety level), and broader personality traits (e.g. I may be prone to pessimistic fantasizing) may negatively affect my performance. On the other hand, as illustrated by Baird and colleagues, mind wandering while preparing for an interview might also turn out to be adaptive—e.g. if it allows me to creatively come up with original ideas or strategies. Another representation of the dual character of mind wandering comes from fiction. In Billy Wilder’s movie The Seven Year Itch (1955), the protagonist Richard Sherman experiences acute and recurring episodes of daydreaming. Throughout the movie, Richard indulges in several episodes of mind wandering that mostly revolve around seducing his new neighbor (interpreted by Marilyn Monroe). In one of his raving monologues, Richard vindicates imagination as one of his most defining character traits: “It’s just my imagination. Some people have flat feet. Some people have dandruff. I have this appalling imagination”. These mind wandering experiences, however, produce positive as well as negative effects. On the one hand, they give Richard—who is normally quite shy and neurotic—the necessary confidence to invite her neighbor over for a drink and then out on a date. On the other hand, they fuel Richard’s paranoid thoughts as he keeps fantasizing about what would happen if his wife were to find out about the (still imaginary) affair.[4]

What distinguishes the cases just described from extreme instances of hypoagency such as AVH? The two phenomena appear prima facie very similar in terms of duration and frequency. On the one hand, patients affected by AVH report that the experience of voice hearing becomes particularly distressing when the voices grow in number and intensity, acting like a “running commentary” of one’s life (Longden 2013). On the other hand, researchers studying mind wandering indicate that subjects “spend almost half a day engaged in the experience” (Smallwood and Andrews-Hanna 2013, 1) or even “roughly two thirds of their lifetime” (Metzinger 2013, 6). A crucial difference between the two cases seems to be the person’s capacity to exercise a sufficient degree of control over the phenomenon. For instance, some aspects related to task-context (i.e. how demanding the activity is) might heavily influence the nature of the mind wandering episode, making it adaptive or disruptive as a result (Smallwood and Andrews-Hanna 2013). When we are engaging in a relatively non-demanding task, the experience of mind wandering is likely to be less disruptive and more conducive to positive outcomes (e.g. creative solutions) because our mental resources need not be fully absorbed in the completion of the task at hand. Conversely, when the current task requires our undivided attention an episode of mind wandering qualifies as a distressful interruption. Therefore, one’s ability to regulate the context in which mind wandering episodes occur appears to play an important role: one might learn to confine mind-wandering to non-demanding situations— e.g. washing dishes—while fending it off from demanding ones (e.g. work or study). One might also learn to compartmentalize working or study time in order to devote designated unstructured spaces to mind wandering. This strategy appears to be successful as studies on creativity have consistently shown that original solutions to problems are more likely to arise when people allocate some unstructured time to mind wander (Dijksterhuis and Meurs 2006). Lots of interesting examples on how to implement these strategies are offered by the comedian John Cleese in his lecture about creativity (1991). While planning his weekly work schedule, Cleese makes sure to always leave a couple of slots open for creative thinking and treats them as serious commitments on a par with meetings, appointments, etc. He describes the rewards as extremely valuable: “If you just keep your mind resting against the subject in a friendly but persistent way, sooner or later you will get a reward from your unconscious, probably in the shower later. Or at breakfast the next morning, but suddenly you are rewarded, out of the blue a new thought mysteriously appears” (Cleese 1991).

Notably, the process of gaining control over internally generated thoughts and speech acts is similar to the one described by recovering AVH patients. For instance, Longden (2013) learns to incorporate the voices in a larger autobiographical narrative and starts regarding them as neglected parts of her own self. Similarly, one of the patients treated by Romme and Escher (2013) talks about setting boundaries and being able to push back the unwanted intrusions to a later time: “I was already able to talk back to my voices with my thoughts, but I learnt to make a specific time of day, the evening, when I would focus, and simply tell the voices ‘later’ if they came at another time” (263). The ability to exercise a certain degree of control within a paradigmatically uncontrolled activity may therefore be crucial to distinguish between ordinary, or even adaptive, cases of mind wandering and their pathological counterparts.

2.2 Hyperagency: False Confessions

False confessions are usually characterized as situations in which someone confesses to a crime that he or she has not committed, or significantly overstates his or her involvement during custodial interrogation (Gudjonsson 2003). These cases qualify as instances of hyperagency because someone who falsely confesses to a crime incorrectly self-attributes an action that someone else has actually performed.

The idea of non-mentally disordered people willing to face legal charges for something they have not done appears very counterintuitive. Yet, studies in forensic psychiatry show that false confessions are relatively frequent, although their exact number is obviously difficult to determine. For example, in the early Eighties 10% of the defendants assessed in Birmingham and 24% of those in the London pleaded “not guilty” at their trial after having provided the police with a written confession (Gudjonsson 2003, 184). In his extensive work on the topic, Gudjonsson shows that false confessions are not confined to the mentally ill and that “the view that apparently normal individuals would never seriously incriminate themselves when interrogated by the police is wrong” (Ibid., 243). Forensic psychologists usually group false confessions into three categories: a) voluntary, where one spontaneously confesses without being interrogated, either to protect someone else or for pathological reasons— e.g. self-punishment; b) coerced-compliant, where one confesses as the result of an interrogation to obtain some immediate gain—e.g. escape from an intolerable situation, having one’s sentence reduced; c) coerced-internalized, where one confesses as the result of an interrogation because he comes to believe that he has committed the crime (Gudjonsson 2003, 192-195). Obviously c) cases are the most relevant to our purposes, because they comprise a mistaken self-attribution that the subject genuinely endorses. However, the discussion of real-life examples shows that the boundary between b) and c) is not always clear-cut.

A famous case of coerced-internalized false confession is the one portrayed in Ava DuVernay’s series When They See Us (2019) which involves the men who came to be known as the “Central Park Five” (and later as the “Exonerated Five”). The series covers the prosecution and incarceration of five males of color, following the rape and assault of a white woman in Central Park in 1989. The first episode is almost entirely devoted to the interrogations of the five suspects and provides several insights on how their false confessions came about. Following the trial, the five teenagers received sentences ranging from five to fifteen years in prison, until the actual perpetrator confessed to the rape in 2001 and the men were finally released.

The way in which the Exonerated Five came to confess to a crime that they did not commit shows that the issue is quite complex. First, the methods used by the police during the interrogation play an important role, as well as the conditions in which the custodial confinement occurs—e.g. sleep-deprivation, under- or over-stimulation, inadequate diet and physical discomfort. Some studies suggest that interrogation techniques may be responsible for eliciting memory distrust and distortion when combined with situations of emotional shock or extreme stress (Henkel and Coffmann 2004). The case of the Exonerated Five is particularly illustrative in this respect. Kevin Richardson, who was 14 at the time, was kept in police custody and interrogated for 18 hours nonstop without any family member present. Raymond Santana spent most of the interrogation in the presence of his grandmother, who did not speak English and only received spotty translations about crucial details of the crime. Antron McCray’s father was blackmailed by a police officer because of a past conviction that might have cost him his job, and ended up convincing his son to confess: “I want you to do what the police wants you to do. You need to say what they want you to say”.

Second, false confessors usually exhibit a set of traits that make them particularly vulnerable to suggestion: young age, low self-confidence, exaggerated trust in authority, eagerness to help and difficulty in detecting discrepancies between what is recalled and what is suggested (Ofshe 1989). Again, this is apparent in the Exonerated Five case, where the young age of the suspects (ranging from 14 to 17), the techniques of brutal coercion employed by the police, and the racially-informed power dynamics played a crucial role. In DuVernay’s series, the suspects are effectively manipulated by the detectives, who play them against one another in order to obtain partial confessions that would allow them to incriminate the group as a whole. Police officers use a variety of techniques that make it difficult to understand whether the resulting confessions would be merely compliant or also (partially) internalized. For instance, they pressure suspects by falsely claiming that others have already confessed and incriminated them (“‘Ray did it’, that’s what they say”), they blackmail them (“The sooner you tell us, the sooner you go home”), and they ask leading questions (“Who took off her shirt? Was it Antron?”). This way five people end up confessing to a crime they neither committed nor witnessed, either by admitting partial involvement (“It was like, I came over to where everybody was at and where the lady was at, and I was trying to stop it and help her out, and I think, no… she scratched me, that’s how I got the scratch”, Kevin Richardson) or by fully confessing (“This is my first rape”, Korey Wise).

What makes false confessions different from the instances of pathological guilt discussed above? There are some striking similarities between the two situations: in both cases, a subject falsely, although sincerely, comes to believe that s/he has done something that falls beyond his/her control, and takes moral as well as legal responsibility for it. In this sense, both internalized false confessions and cases of pathological guilt hinge on incorrect self-attributions originating from false memories.[5] Moreover, a strong feeling of guilt features in both kinds of confessions. Many false confessors, for instance, feel guilty for not having been in control when the crime was committed (e.g. because of alcohol or drug intoxication), or for not being able to trust their memory in recalling events without confusion (Gudjonsson 2003). Despite these similarities, mentally disordered subjects appear to exhibit a pre-existing feeling of guilt that makes some of their actions particularly salient (e.g. Emmy von N), while false confessors experience guilt after having lost confidence about their ability to recollect what happened. As a consequence, the degree of internalization with respect to their confession differs; while voluntary confessions are rarely retracted, coerced-internalized confessions are usually taken back by the subject even if the timing of retraction varies from a few hours to several years (Gudjonsson 2003). In this sense, duration can be taken as a reliable indicator to distinguish between extreme and intermediate cases: the least pressured and the hardest to retract the confession, the higher its pathological import. This also leaves room for borderline cases: some false confessions may be characterized as transitory mental disorders from which people recover soon after the stressful situation has ended, while longer processes may indicate that the person has crossed a clinically relevant threshold.

Pathological and non-pathological cases may also differ in terms of urgency and intensity. For instance, psychotic subjects voluntarily contact the police and appear distressed for having committed the crime in question (“I did it”; “It was me”), whereas false confessors initially proclaim their innocence and then come to confess in a tentative fashion (“I must have done it”; “I think I did”). Protective factors such as strength and control play an important role as subjects often confess after a prolonged period of physical discomfort and psychological stress. Gudjonsson describes the process as follows: “The forces pushing people towards confessing are strengthened (e.g. persuading people that it is in their own interest to confess, that there is substantial evidence to link them to the crime) whilst forces maintaining resistance are weakened (e.g. by tiredness, lack of sleep, exhaustion, emotional distress)” (2003, 189). In this sense, one important difference between pathological and non-pathological cases may lie in the degree of effort required by the subject to regain a sufficient level of control over the situation. In some cases, the state of confusion and memory distortion leading to the false confession would fade quite easily, while in others the recovery process may take longer or fail to occur at all.

3. Concluding Remarks

In this paper I discuss disorders of agency as cases in which people encounter difficulties in assessing their own degree of responsibility (self-attribution), and/or as disturbances in their sense of being in control of their actions (feeling of agency or control). I substantiate the idea that agency should be conceived in dimensional terms by discussing examples where agency may be seen as “too little” (hypoagency) or “too much” (hyperagency). Notably, extreme cases of hypo- and hyper-agency map onto phenomena that are usually conceived as disordered, such as AVH or pathological guilt. However, seeing agency on a spectrum also allows us to discuss intermediate cases in which the sense of being in control is disturbed without giving rise to clinically relevant manifestations. Although some intermediate cases may still turn out to be problematic (e.g. false confessions), I show that others exhibit an adaptive nature in many circumstances (e.g. mind wandering). Discussing these examples also contributed to a better understanding of how different aspects of agency can come apart. For instance, in AVH both self-attribution and the feeling of agency appeared to be disrupted; in other cases—such as mind wandering—self-attribution is usually correct while the subject experiences a feeling of diminished control with respect to the relevant thoughts or actions. Obviously, there are many other cases that could be assessed along these dimensions and the examples discussed here are not meant to be exhaustive. In the synthetic table below, I provide some further suggestions as well as a summary of the examples discussed in the paper.

Another core aspect of my discussion concerns the role played by quantitative factors such as duration, frequency, or intensity when it comes to distinguishing intermediate and extreme cases. These factors may play an important role in clinical practice, as they allow clinicians to improve case formulations and diagnoses of borderline or at-risk cases (Fusar-Poli et al. 2013). The focus on quantitative factors would also contribute to better track “the course of an illness” in longitudinal assessments, by monitoring how a patient’s sense of agency evolves over time and in correspondence of turning points such as onset, development, relapse, and (possibly) remission (McGorry et al. 2018). The work I propose here on the sense of agency is part of a broader project that includes multiple dimensions (i.e. familiarity, confidence, salience) that may come to be altered in different circumstances, giving rise to clinically relevant conditions. In this sense, agency should be taken as only one of the relevant dimensions of functioning whose extreme disruption gives rise to mental conditions as we know them. At the same time, embracing a dimensional approach also implies acknowledging that “disordered” states are only quantitatively different from “normal” ones, and that the boundaries around normality and pathology are unlikely to be discrete and clear-cut.

Acknowledgments

The original version of this paper benefitted from discussions with Heidi Maibom, Peter Langland-Hassan, Thomas Polger, and Johannes Brandl. I would like to thank Agustín Vicente, Marta Jorba, Cecilia Fava, and Nicola Falde for offering insights on different aspects of the paper. I am also grateful to Emiliano Loria and two anonymous referees of EuJAP for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

Valentina Petrolini’s research is supported by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, postdoctoral fellowship FJC2018-036191-I, by Agencia Estatal de Investigación, grant number: PGC2018-093464-B-I00; by the Basque Government, grant number: IT1396-19; and by the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), grant number: GIU18/221.

REFERENCES

Alderson-Day, B., S. McCarthy-Jones, S. Bedford, H. Collins, H. Dunne, C. Rooke, and C. Fernyhough. 2014. Shot through with voices: Dissociation mediates the relationship between varieties of inner speech and auditory hallucination proneness. Consciousness and Cognition 27: 288-296.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.05.010.

Allen, P., D. Freeman, L. Johns, and P. McGuire. 2006. Misattribution of self-generated speech in relation to hallucinatory proneness and delusional ideation in healthy volunteers. Schizophrenia Research 84(2–3): 281-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.01.021.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R. 2012. The brain’s default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. The Neuroscientist: A Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry 18(3): 251-270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858411403316.

Baird, B., J. Smallwood, M. D. Mrazek, J. W. Y. Kam, M. S. Franklin, and J. W. Schooler. 2012. Inspired by distraction: Mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychological Science 23(10): 1117-1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612446024.

Bortolotti, L., and K. Miyazono. 2015. Recent work on the nature and development of delusions. Philosophy Compass 10(9): 636-645. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12249.

Cleese, J. 1991. Lecture on creativity. Video Arts.

Dijksterhuis, A., and T. Meurs. 2006. Where creativity resides: The generative power of unconscious thought. Consciousness and Cognition 15 (1): 135-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2005.04.007.

DuVernay, A. 2019. When They See Us. Netflix.

Fernyhough, C. 2004. Alien voices and inner dialogue: Towards a developmental account of auditory verbal hallucinations. New Ideas in Psychology 22(1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2004.09.001.

Freud, S. 1917. Mourning and Melancholia. Standard Edition 14. London: Hogarth.

Freud, S., and J. Breuer. 1893. On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena: Preliminary Communication. Standard Edition 2. London: Hogarth.

Frijda, N. H. 1986. The Emotions: Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frith, C. D. 2003. The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia. Reprinted. Essays in Cognitive Psychology Series. Hove: Psychology Press.

Fusar-Poli, P., S. Borgwardt, A. Bechdolf, J. Addington, A. Riecher-Rössler, F. Schultze-Lutter, M. Keshavan, et al. 2013. The psychosis high-risk state: A comprehensive state-of-the-art review’. JAMA Psychiatry 70 (1): 107-120. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.269.

Gudjonsson, G. H. (2003). The Psychology of Interrogations and Confessions: A Handbook. John Wiley & Sons.

Gram Henriksen, M., A. Raballo, and J. Parnas. 2015. The pathogenesis of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: A clinical-phenomenological account. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 22 (3): 165-181. https://doi.org/10.1353/ppp.2015.0041.

Henkel, L. A., and K. J. Coffman. 2004. Memory distortions in coerced false confessions: A source monitoring framework analysis. Applied Cognitive Psychology 18 (5): 567-588. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1026.

Hohwy, J. 2004. The experience of mental causation. Behavior and Philosophy 32(2): 377-400.

Hugdahl, K., E.-M. Løberg, L. E. Falkenberg, E. Johnsen, K. Kompus, R. A. Kroken, M. Nygård, R. Westerhausen, K. Alptekin, and M. Özgören. 2012. Auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia as aberrant lateralized speech perception: Evidence from dichotic listening. Schizophrenia Research 140(1): 59-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.019.

Johns, L. C., K. Kompus, M. Connell, C. Humpston, T. M. Lincoln, E. Longden, A. Preti, et al. 2014. Auditory verbal hallucinations in persons with and without a need for care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 40 (Suppl_4): S255-264. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu005.

Jones, S. R., and C. Fernyhough. 2007. Thought as action: inner speech, self-monitoring, and auditory verbal hallucinations. Consciousness and Cognition 16 (2): 391-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2005.12.003.

Lazarus, R. S., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer.

López-Silva, P. 2016. Schizophrenia and the place of egodystonic states in the aetiology of thought insertion. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 7 (3): 577-594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0272-1.

Longden, E. 2013. Learning from the voices in my head. In Monterey, CA: TED Conferences.

Maiese 2015. Auditory verbal hallucinations and sense of ownership. Paper presented at the Southern Society of Philosophy and Psychology: New Orleans.

Mason, M. F., M. I. Norton, J. D. Van Horn, D. M. Wegner, S. T. Grafton, and C. N. Macrae. 2007. Wandering minds: The default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science (New York, N.Y.) 315 (5810): 393-95. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1131295.

McGorry, P. D., J. A. Hartmann, R. Spooner, and B. Nelson. 2018. Beyond the “at risk mental state” concept: Transitioning to transdiagnostic psychiatry. World Psychiatry 17(2): 133-142. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20514.

Metzinger, T. K. 2013. The myth of cognitive agency: Subpersonal thinking as a cyclically recurring loss of mental autonomy. Frontiers in Psychology 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00931.

Naranjo, J. R., and S. Schmidt. 2012. Is it me or not me? Modulation of perceptual-motor awareness and visuomotor performance by mindfulness meditation. BMC Neuroscience 13(1): 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-13-88.

Nayani, T. H., and A. S. David. 1996. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychological Medicine 26(1): 177-189. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329170003381x.

Ofshe, R. 1989. Coerced confessions: the logic of seemingly irrational action. Cultic Studies Journal 6(1): 1-15.

Pacherie, E. 2007. The sense of control and the sense of agency. PSYCH 13: 1-30.

Pacherie. E. 2008. The phenomenology of action: a conceptual framework. Cognition 107(1): 179-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.09.003.

Petrolini, V., M. Jorba, and A. Vicente. 2020. The role of inner speech in executive functioning tasks: Schizophrenia with auditory verbal hallucinations and autistic spectrum conditions as case studies. Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572035.

Plath, S. 1963. The Bell Jar. Faber & Faber

Proust, J. 2006. Agency in schizophrenia from a control theory viewpoint. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2457.003.0006.

Radden, J. 2009. Moody Minds Distempered: Essays on Melancholy and Depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ratcliffe, M. 2010. Depression, guilt and emotional depth. Inquiry 53(6): 602-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2010.526324.

Ratcliffe, M. 2015. Experiences of Depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Romme, M., and S. Escher. 1993. Accepting Voices. London: Mind Publications.

Romme, M., and M. Morris. 2013. The recovery process with hearing voices: accepting as well as exploring their emotional background through a supported process. Psychosis 5(3): 259-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2013.830641.

Saks, E. 2007. The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness. Hachette UK.

Schupak, C., and J. Rosenthal. 2009. Excessive daydreaming: A case history and discussion of mind wandering and high fantasy proneness. Consciousness and Cognition 18(1): 290-292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.10.002.

Smallwood, J., and J. Andrews-Hanna. 2013. Not all minds that wander are lost: The importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Frontiers in Psychology 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00441.

Smallwood, J., and J. W. Schooler. 2006. The restless mind. Psychological Bulletin 132 (6): 946-58. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.946.

Styron, W. 1991. Darkness Visible. Random House.

Szalai, J. 2019. The sense of agency in OCD. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 10(2): 363-380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-017-0371-2.

Toh, W. L., N. Thomas, and S. L. Rossell. 2015. Auditory verbal hallucinations in bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD): A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 184: 18-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.040.

Wegner, D. M., and T. Wheatley. 1999. Apparent mental causation. sources of the experience of will. The American Psychologist 54 (7): 480-492. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.54.7.480.

Wilder, B. 1955. The Seven Year Itch. Twentieth Century Fox.

Endnotes

- In this paper I treat “agency” and “control” as synonymous, although I am aware that some finer-grained distinctions may be drawn between them (Pacherie 2007). For the purposes of my discussion, the feeling of agency and control seem to go hand in hand: gaining or losing control fundamentally implies augmenting or deteriorating one’s sense of agency. As a consequence, the two notions cannot significantly come apart, i.e. one cannot be in control without at the same time experiencing a sense of agency. ↑

- Another pathological case of hypoagency would be Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), where subjects experience being compelled to act in a particular way or report a sense of performing an uncontrollable action (Szalai 2019). Yet, as opposed to what happens with AVH, OCD subjects tend to self-attribute actions correctly while experiencing a diminished sense of agency/control. In this sense, OCD may qualify as a clinically relevant, but less extreme disorder of agency. ↑

- See Lazarus and Folkman (1984) for a detailed discussion on dual factors, i.e. factors that act as risk-inducing or protective depending on the context. ↑

- One might argue that even in these milder cases agency is impaired: we can’t get rid of the song stuck in our head, Richard Sherman cannot control his daydreaming episodes, etc. I do grant this point, although there seem to be different degrees of severity at play. Although in mind wandering cases the feeling of agency is surely diminished, correct self-attribution is preserved: that is, we perceive the tune as “popping up from nowhere” but not as externally generated or inserted by someone else in our mind. By contrast, in extreme cases (such as AVH) the sense of agency is so disrupted that we completely lose the sense of what is self-generated and within our boundaries. Nothing in my account prevents this from happening with songs, provided that self-attribution also becomes incorrect and the song is then perceived as inserted, implanted, etc. ↑

- Assessing the degree of agency/control in these situations is obviously complex given that past events are involved. One option may be that false memories themselves originate from a disturbance in the sense of agency/control applied to the past. Alternatively, such a disordered sense of agency/control may apply to the subject’s own thoughts in the process of recollection, which might make it more difficult to distinguish between real and imagined (or witnessed) events. In this sense, internalized false confessions would be quite similar to illusion of control cases (Wegner and Wheatley 1999; Hohwy 2004), where agency misattributions are not simultaneous with the action but rather occur at a (slightly) later time. ↑